NDC 2014 Oslo, Core software design principles, TDA, OCP, LSP and DIP

Another set of core design principles by Venkat Subramaniam.

Tell Don´t Ask Principle, TDA

You want to tell a piece of code to do stuff, rather than asking a piece of code for some information and then going back and doing it.

It is violated in so many places because we usually don´t think about it explicitly.

Let´s put one simple example: We have a collection of books and we want to print information about these books

var books = new List<Book>();

for(int i = 0; i < books.Count; i++)

{

books[i].PrintInformation();

}We are violating TDA principle: we are going to the collection of books and asking hey books, give me your count. Books say, Ok, here is my count, I don´t know why but here we go. One again, inside the loop we go to the books and ask for a low level detail (the element of the ith position).

But how do we do things in the real world? If somebody comes and say: hey, what are you doing tomorrow? my usual answer is: what do you want?! because you don´t know what he wants. He is asking for a low level detail.

But let´s go back to the book example, how do we commit to TDA principle?

var books = new List<Book>();

books.Select(b => b.PrintInformation());We go to the books collection and tell, _hey, print you books´ information. We are telling not asking. The new logic is:

- More readable.

- Let´s work to do an action.

- Concise and elegant.

- Easier to modify: if in the future we have to modify it, we code is in one place.

- Easier to find and to fix bugs

Similarly, when we design our classes, rather than providing methods that are query methods, methods that affect the state of the object, we should write methods that actually perform the task and give back a result.

This is what we call encapsulation in Object Oriented Programming. Furthermore, if we remember getter and setter methods, that expose state of an object and those tiny little details, those don´t follow at all the TDA principle.

As we say, it is a little bit more difficult to follow but every time we have a piece of code, we can just stop by and say: Am I following TDA?

Open Closed Principle, OCP

A software module must be open for extension, but closed for modifications.

It sounds a bit weird. In other words it says that a module must be able to do some more things that what it did before, but without actually changing it. I always think in a turtle when I think in this principle:

A turtle is Closed for modifications, it has been evolving the shell mechanism for centuries, it is well proved, we can´t change it. But it is opened for extension, we can add new features on top of the shell, like adding spikes in the shell to make it a super turtle:

That´s alright but we know things in code are not that easy. Let´s do a little example to understand it.

Let´s say we have an application that creates cars, we define a car with a couple of properties, and a simple Engine:

class Engine

{

}

class Car

{

public int Year {get; set;};

public Engine Engine {get; set;};

public Car(int theYear, Engine theEngine)

{

Year = theYear;

Engine = theEngine;

}

public override string ToString()

{

return string.Format("{0} {1}", Year, Engine);

}

}

class Sample

{

static void Main(string[] args)

{

Car car1 = new Car(2014, new Engine());

Console.WriteLine(car1);

}

}So far so good. Let´s say that we need to create a new car based on a previous car, thus we need a copy constructor

class Engine

{

public Engine(){}

public Engine(Engine other){}

}

class Car

{

public int Year {get; set;};

public Engine Engine {get; set;};

public Car(Car otherCar)

{

Year = otherCar.Year;

Engine = new Engine(otherCar.Engine);

}

public Car(int theYear, Engine theEngine)

{

Year = theYear;

Engine = theEngine;

}

public override string ToString()

{

return string.Format("{0} {1}", Year, Engine);

}

}

class Sample

{

static void Main(string[] args)

{

Car car1 = new Car(2014, new Engine());

Console.WriteLine(car1);

Car car2 = new Car(car1);

Console.WriteLine(car2);

}

}Notice how we need to create a new Engine for the new car, instead of assigning the previous reference. That would be a shallow copy of the Engine and both cars would have the same Engine. But let´s say that there is another type of Engine in the market in addition to the regular one, a TurboEngine. We need to support it in our car´s application. It is an Engine but it adds to Turbo mechanism. Therefore we decide to inherit from Engine.

class TurboEngine : Engine

{

public TurboEngine(TurboEngine other) : base(other)

{}

}Notice how we provide a copy constructor that only delegates to the Engine base constructor. Question is: Is it legal to create car1 in the previous code to use a TurboEngine? Will the compiler be happy? Answer is: Yes, a TurboEngine is still an Engine so when we create the car, it will assign an Engine that in this case happens to be a TurboEngine:

class Sample

{

static void Main(string[] args)

{

Car car1 = new Car(2014, new TurboEngine());

Console.WriteLine(car1);

Car car2 = new Car(car1);

Console.WriteLine(car2);

}

}But what happens when you start running your cars? So the first car has a TurboEngine but the second one has a regular Engine, the copy constructor for the car didn´t make the right copy of the Engine. How do we fix it? Let´s go and fix the Car´s copy constructor:

public Car(Car otherCar)

{

Year = otherCar.Year;

if(otherCar.Engine is TurboEngine)

{

Engine = new TurboEngine((TurboEngine)otherCar.Engine);

}

else

{

Engine = new Engine(otherCar.Engine);

}

}What do you think about this solution? This is wrong. It fails the Open Closed Principle: Every time you add a new type of Engine you have to change the code. The is statement up there is using reflections to inspect the type. There was a time where languages resisted to include it because they thought it would make the code less extensible.

How do we fix it? One way is to make the code polymorphic by adding a Clone method in the Engine.

public Car(Car otherCar)

{

Year = otherCar.Year;

Engine = (Engine)otherCar.Engine.Clone();

}Because it is polymorphic, every type of Engine will have its own Clone implementation. If the Engine was a Turbo one the copied car would have TurboEngine.

There´s still a problem with that Clone method in C#: if we make the Engine a readonly property it can be assigned in the initialization and in the constructor, but not in Clone. It may be solved by providing your own implementation of Clone in the Engine and that will return a call to the constructor. Bear in mind that when we needed to add a TurboEngine, that was the point where we needed to solve the problem and add the latest solution, not before, we don´t want premature solutions (remember YAGNI Principle).

So we saw the OCP and an example of how we can break it. But the complexity of the OCP is that it can be broken in so many ways so we should be putting extra caution not to break it.

Liskov´s Substitution Principle, LSP

I always thought that this principle has a really bad name so its hard to remember. It says:

Use Inheritance only when you mean substitutability.

We know inheritance is one of the most abused concepts in programming, because it makes really easy to reuse functionality. But inheritance is not only for reusing things. This principle tries to enforce some constraints to use inheritance. In other words:

- We have a class A.

- We have a class B.

- We should inherit B from A, only if anywhere an instance of A used, an instance of B can also be used.

- That means that external behavior of B must be compatible with external behavior of A.

- We should use inheritance for re-usability. If your intention was to use the implementation of A in the implementation of B, then use delegation instead of inheritance.

Let´s put an example of this, a class vector that allows us to add stuff or remove stuff from anywhere in the collection:

class Vector<T>

{

public void AddStuff(T element);

public T TakeStuff();

}Imagine we can along defining a Stack, which uses the Last-In-First-Out (LIFO). Because we don´t want to duplicate functionality and reuse Vector´s functionality, inherit from Vector makes things really easy:

class Stack<T>

{

}Do you think this is a bad idea? Imagine we have a piece of code uses a vector, it creates it and deals with a vector as it is supposed to be used:

Then we have another piece that uses a stack:

class Main

{

public void LatestMoviesViewer()

{

MoviesRepository movies = new MoviesRepository(new Stack<Movies>());

Movie lastestMovie = movies.GetMovie();

latestMovie.Watch();

}

}

class MoviesRepository

{

private Stack<Movie> _movies;

public MoviesRepository(Stack<Movie> movies)

{

_movies = movies;

}

public Movie GetMovie()

{

return _movies.TakeStuff();

}

}We have a viewer to see the latest movies and it uses a stack of movies because the latest movies should be the ones that should be first out. But when we use this code we see a problem: the latest movies viewer is giving me any movie in the middle. The problem is that since a stack of movies is a vector of movies, stack says: no problem I´m a vector as well so I can be used anywhere the vector is used. The vector doesn´t know it is a stack so it should give the the last movie. Then the stack thinks: I feel violated.

We could fix this problem a number of ways but the problem is behind the scenes, it is a big design problem in Stack class. But don´t feel bad about yourself, if you go to google and search for the Stack implementation in the JDK, you find this:

Now we know that wasn´t a great idea:) Remember Liskov´s principle, despite its name it imposes a big boundary when it comes to use inheritance, a boundary that can be very easily broken.

Dependency Inversion Principle, DIP

Let me tell you a story to explain this principle:

Imagine somebody that used to travel a lot. Some day in the nineties he went to a hotel. He needed to wake up very early the day after. He was going to set an alarm when he noticed there wasn´t any clock in the hotel. He walked to the Reception and asked:

-Excuse me, is there any clock in the rooms?

-No, there isn´t but you can use the television. You can set the television to start in the time you want to wake up.

-Are you sure it will work?… Ok, I´ll try it.

Our guy went back to his room and since he was a software developer he tried it a few times. He set it to start a few minutes later and all seemed to work. When he was confident enough he finally set 6AM in the television and gone to sleep.

It was 6PM when he woke up, listening some weird voices in the room. He was a bit scared, somebody was inside the room. He saw his television, it was running with some morning news program. He was abroad so he couldn´t understand. Suddenly he remembered it all: he had set the television as a clock.

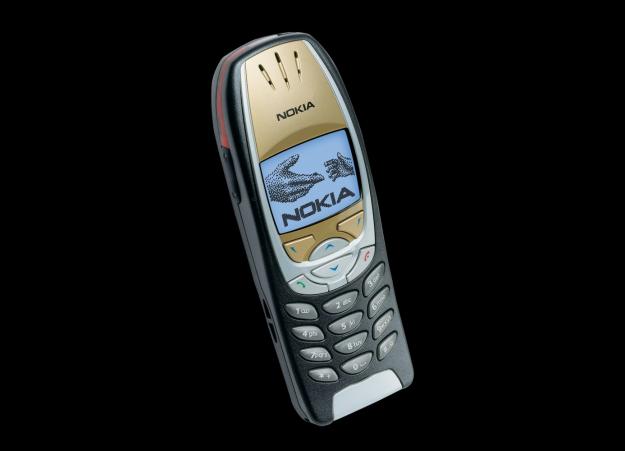

A few years later after that episode in the hotel, he experienced the same problem. But he had one of that latest Nokia 6210 mobile phones. He took a look at the settings of the phone trying to find if there was an alarm there. Voilá, there it was a nice alarm configuration with a lot of tools to set it up.

So finally it all made sense, he though: my coupling was wrong, I didn´t need a clock, or a mother, or a phone, what I needed was something to wake me up. Then he remembered those days where he was at school, he didn´t even need a clock by his bed. He had a lovely mother, not so lovely when he needed to wake up for his classes. She would go and wake him up, even if throwing some water was required.

That´s the Dependency Inversion Principle:

Rather than depending on a concrete implementation you should depend on abstractions.

So that´s the set of principles I wanted to explain. Hope you find it useful. Talk you soon!

Happy coding!